High-Risk Citizens

A software is used for detecting potential benefit cheats in the Netherlands. The government keeps quiet about how that works. Civil rights activists are taking the matter to court.

By Ilja Braun

Capelle aan den Ijssel is a Dutch town on the edge of Rotterdam. If one took the town administration's word for it, you’d better stay away from the municipality of 66,000 residents. Allegedly, the place suffers from an "erosion of values and norms" in "multi-problem families" who are "mainly occupied with surviving on a day-to-day basis". A disproportionally large share of council housing and fading social cohesion, paired with work migrants who only stay temporarily and often do not report their residence, lead to moonlighting in illegal garage workshops, illicit trade of baby food, debt problems, truants and child poverty. Sodom and Gomorrah in the Tulip State? Surely, many people outside the Netherlands have quite a different picture of the country.

For a long time, the Netherlands were famous for their welfare state. When things were going well for the small country, it was possible to live carefree off social and unemployment benefits. If you didn't want to work, you weren't really forced to. Nowadays, the Dutch government's all-round care system has been scaled back and replaced by appeals to self-responsibility. What's more, the Dutch authorities are using far-reaching technical facilities to identify citizens who may be cheating the state by cashing in on wrongfully collected housing, unemployment or other benefits, committing tax fraud, moonlighting or illicit trafficking.

System Risk Indication (SyRI)

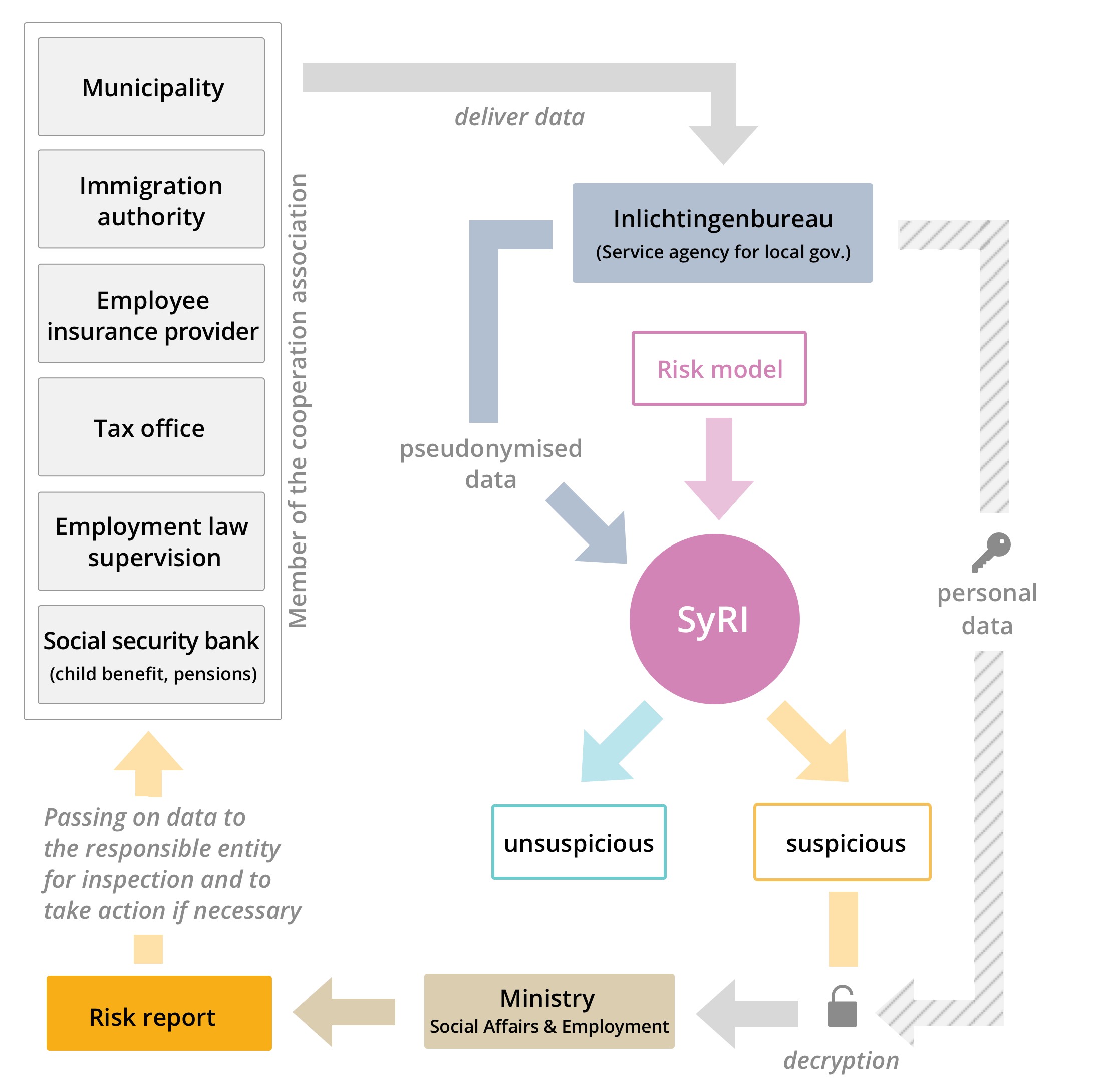

The magic word is SyRI: System Risk Indication, a big data analysis system. Citizen data stored by various authorities and state institutions are combined and analysed. I.e., tax data can be compared with information on who receives state aid and support. Or information on the place of residence with data from the naturalisation authority. Based on certain risk indicators, the software allegedly detects an "increased risk of irregularities", i.e. whether someone is acting against the law. Thus, SyRI would set off an alarm if someone received housing benefits but was not registered at the address in question. An employee from the Ministry of Social Affairs would then take a closer look at the data. If they believed that something could be amiss, a "risk report" would be made, which is passed on to the relevant authorities. The agency responsible for housing benefits would send an inspector to the "risk address" in question. If the suspicion is confirmed, the state aid can be reclaimed.

How does SyRI work? An Example from Haarlem

If a cooperation association of different state agencies uses SyRI, the output is forwarded to the so-called Inlichtingenbureau. This service agency, which is actually there to help local authorities determine whether citizens are entitled to state benefits, acts as a data processor on behalf of the Ministry of Social Affairs and Employment. First, the data is merged at the Inlichtingenbureau. Then the personal data is encrypted and a separate dataset with the keys is created for later decryption. The data is analysed based on a risk model in SyRI. Only those data records where the system flags something are decrypted and forwarded to the Ministry of Social Affairs and Employment. This is where the "risk reports" are created. (Image: CC-BY, AlgorithmWatch)

Undermining the Principle of Purpose Limitation

For Tijmen Wisman, chairman of the civil rights NGO Platform Bescherming Burgerrechten (Platform for Civil Rights Protection), this clearly goes too far. The data protection principle of purpose limitation is turned on its head because it is not defined for which purposes the data was collected. And to make things worse, individual citizens are not even informed if the software classifies them as a "high-risk citizen". "You end up in a register and get a score for a certain risk," says Wisman. "On the basis of the data in this register, decisions are made that affect you personally as an individual. But you don't even know that you're in the register or what consequences that can have for you personally."

Does this mean that the Netherlands are a surveillance state? It’s obvious that many things are done differently there compared to other countries. So-called "intervention teams" have existed in the Netherlands for around 15 years: police, tax authorities, the public prosecutor's office, immigration authorities, the service providers for employee insurance, social security and local authorities have been working together in interdisciplinary teams to intervene in socially deprived areas. This is not necessarily meant as a repressive approach. It is no secret that crime and social problems are often connected. Different authorities working together in this area can also be of advantage – social issues are not just left to the police.

But what if those who work together in teams now also merge the citizen’s data to form profiles – is that a breach of privacy, or rather the extension of a cooperative approach?

Legal Basis

It’s impossible to say because those who apply for the use of SyRI for their community probably do not know exactly how SyRI works, where its application makes sense or how significant the data and the models really are. At least, this information is not mentioned in the requests they filed in order to be allowed to use the system. An implementing provision to the Dutch Labour and Income Implementation Structure Act stipulates that 17 categories of personal data may be processed within the framework of a SyRI project. (Chapter 5a SUWI). The list ranges from employment data, information on fines and tax data to data of state support services, information regarding the place of residence, data from the naturalisation authority, data concerning reintegration at work after a long illness and personal debts up to information on the health insurance status. According to civil rights activist Tijmen Wisman, there had been no intensive discussions on the new regulation; on the contrary, the regulation was "simply waved through" by Parliament in 2014.

Increased Risk

Video of NGO "Bij Voorbaat Verdacht"

But what criteria does the software use to assess whether there is an increased risk of welfare abuse? An organization called Bij Voorbaat Verdacht ("Suspected from the outset") tried to prise this out with a freedom of information request. The Ministry's answer:

"The risk model is a collection of one or more sets of related risk indicators that may be combined to assess the risk that certain natural or legal persons are not acting in accordance with applicable law. If one were to disclose what data and connections the Inspectie SZW is looking for, (potential) lawbreakers would know exactly on which stored data they would have to concentrate".

And the results? Have the SyRI projects up to now really made a significant contribution to combating welfare abuse, tax fraud or violations of labour law? In a reply to a request by AlgorithmWatch, the Dutch Ministry of Social Affairs and Employment says that results are only available for a single project so far, namely for the operation in Capelle aan den Ijssel described above. There were 113 risk reports for this project, according to the ministry, "which triggered various measures. The identified violations of the law have resulted in the discontinuation or recovery of state benefits and allowances in a total volume of 496,000 euros (including subsequent savings)".

[su_box title="When and How is SyRI Used?"]SyRI is not used throughout the whole of the Netherlands, but only at the specific request of a so-called co-operation association. The request for such a cooperation usually comes from a municipality whose administration would like to work together with other administrations, such as the social insurance carrier for employees or the tax authorities. The goal is defined by law: To combat or prevent the unlawful use or recourse to public money or social security institutions or other income-related state benefits. In addition, action is supposed to be taken against tax and duty fraud and labour law violations, such as moonlighting, but also against illegal exploitation of labour.

According to official data, SyRI has been applied four times so far: in addition to Capelle aan den Ijssel also in Eindhoven, and projects have been running in Haarlem and Rotterdam since 2018. In an industrial area in Eindhoven, according to the applicants, "neglect is to be noted. So far, the municipality of Eindhoven has not sufficiently succeeded in gaining an overview of the developments and steering them in a positive direction”. With a "risk-oriented approach", the plan was to " break through the intimidating climate and contribute to improving the quality of life in this district and the industrial area". This should be done by using the data "required for the 'Neighbourhood-centred approach' risk model built into SyRI". "It was determined that the use of the respective data is necessary to achieve the objectives of the project." In Haarlem, data is compared coming from the municipality, the tax office, the employee insurance provider, the social security bank responsible for child benefit and pensions, the immigration authority and the Inspectie SZW, which is responsible for the prosecution of labour law violations. "This may reveal unlikely data combinations that give rise to further investigations," the application states.

However, trying to find out exactly how the SyRI software is supposed to contribute to solving these problems, the only answer is that thanks to a "risk analysis" supported by SyRI, "a selection of risk addresses" is going to be provided. The inspectors of the agencies and authorities do not seem to know where to start. That’s why it comes in handy if the software suggests names and addresses of people for whom there is any irregularity in the data.[/su_box]

How reliable is SyRI?

To avoid unjustifiably suspecting people, the data is examined for so-called "false positive" signals, as Ministry spokesman Ivar Noordenbos explains to AlgorithmWatch: "Since the data is linked automatically in accordance to a pre-defined risk model, it can happen that a risk is wrongly indicated because of imperfections in the model. To give a fictitious example: Assuming that the model would not be familiar with the concept of retirement homes, then recipients of the basic state pension could be suspected of living in a common household without having reported this. After all, they all have the same address. A data analyst at Inspectie SZW therefore first examines the software's signals for such obviously false risk signals so that no risk reports are generated. In this example, the data analyst would notice that the situation of the recipients of a basic state pension is different than presumed. The corresponding data would be sorted out as 'false positives' so that they would not be used in any subsequent checks. Such false signals are also used to adjust the risk model as far as possible so that the corresponding error does not occur again”. According to the Ministry, however, 62 of the 113 cases in Capelle aan den Ijssel have not been found to be in violation of any law.

Human Rights Violated?

A group of several civil rights initiatives recently filed a landmark case against the use of the software. It is in the first instance; a trial has not yet taken place. The civil rights activists claim that SyRI places citizens under general suspicion and violates the European Convention on Human Rights. The legal powers for invading privacy had been structured so unrestrictedly by the legislature, say the activists, that they could no longer be brought into line with Article 8 of the Convention on Human Rights, which was intended precisely to guarantee the protection of privacy.

The Ministry of Social Affairs and Employment declined to comment on the current proceedings. If the procedure were successful, the part of the law that concerns the use of SyRI would have to be declared unlawful. It would then have to be amended or even be completely abolished. The Dutch government would have to put its risk profiling on hold. It is still unclear, however, whether the civil rights initiatives can sue SyRI at all or whether a person directly affected would have to prove that their fundamental rights had been violated. As long as it is not known just how SyRI works, proving exactly that should be extremely difficult.

Translation by Louisa Well

---

This story was made possible with the support of Bertelsmann Stiftung

Did you like this story?

Every two weeks, our newsletter Automated Society delves into the unreported ways automated systems affect society and the world around you. Subscribe now to receive the next issue in your inbox!