This man had his credit score changed from C to A+ after a few emails

A 52-year-old man in Hanover, Germany, discovered that he’d been erroneously scored by a credit bureau. His story reveals the gaps in credit score regulation.

In October 2019, Mark Wetzler searched for a new electricity provider on a comparison website. He found one, asked for contract and didn’t think more about it. Two days later, he received a letter from the utility company telling him that his contract was denied. His credit score was too low.

Mr Wetzler was taken aback by this answer. At 52, this well-to-do man living in the center of Hanover, a large German city, says that he never missed a payment in his life. Except once, in 1987, when the student stipend he received from the state was transferred too late to his bank account.

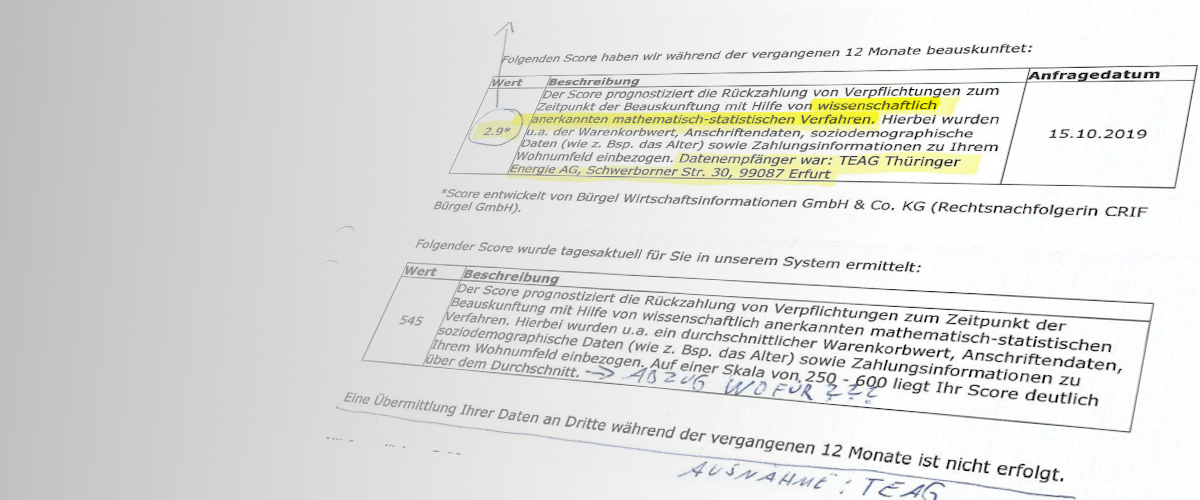

He asked the company that calculated his credit score, CRIF Bürgel, for an explanation. In November, they sent a letter showing that his score was a C. The score was based on information from a telecom company, online marketing firms and “payment data near his address”. Curiously, the same letter mentioned that CRIF Bürgel knew of no “negative” information about him. Why Mr Wetzler’s score was so low remained a mystery.

Five months and several emails later, in March 2020, CRIF Bürgel finally provided an explanation. When he applied for an electricity contract in October, Mr Wetzler probably made a typo (he says it's unlikely but can't tell for sure). The request was made for a Mr “Wetzer” (without l), at the same address. This, according to CRIF Bürgel, explains everything and releases them from any responsibility in the matter. They nevertheless sent a new score to the electricity company, now an A+.

The story could end with the typo. But the November letter was sent to Mr Wetzler (correctly spelled) and, as CRIF Bürgel themselves wrote, such simple typos are routinely and automatically corrected.

This leaves three possible explanations:

- CRIF Bürgel does not check for typos in names before it sends a credit score, but checks it afterwards,

- CRIF Bürgel provides different scores for people it knows to be identical, depending on how their name is spelt, or

- CRIF Bürgel used erroneous data when computing Mr Wetzler’s score.

Given that CRIF Bürgel vehemently denies any wrongdoing, the third hypothesis can be left out.

If any of the first two explanations are correct, it is hard to figure how they square with Germany’s legislation on credit scores, which only allows the computation of an individual’s likelihood to repay a loan if it follows a “scientifically valid mathematical-statistical process”. Unless, of course, it could be demonstrated that people who misspell their names are less likely to repay a loan ; in which case the second explanation above would be legitimate.

The data protection authority of Bavaria, which oversees the credit scoring activities of CRIF Bürgel, did not reply to several requests for comment.

In 2018, AlgorithmWatch and the Open Knowledge Foundation Germany conducted a large investigation of credit scores in Germany, the OpenSchufa project. The research showed that the oversight of credit bureau was, at best, inadequate. Mr Wetzler’s story shows that little has changed since.

Disclosure: AlgorithmWatch receives funding from the Bertelsmann Stiftung, which owns the Bertelsmann Group, which owns Arvato, which operates a credit bureau.

Did you like this story?

Every two weeks, our newsletter Automated Society delves into the unreported ways automated systems affect society and the world around you. Subscribe now to receive the next issue in your inbox!