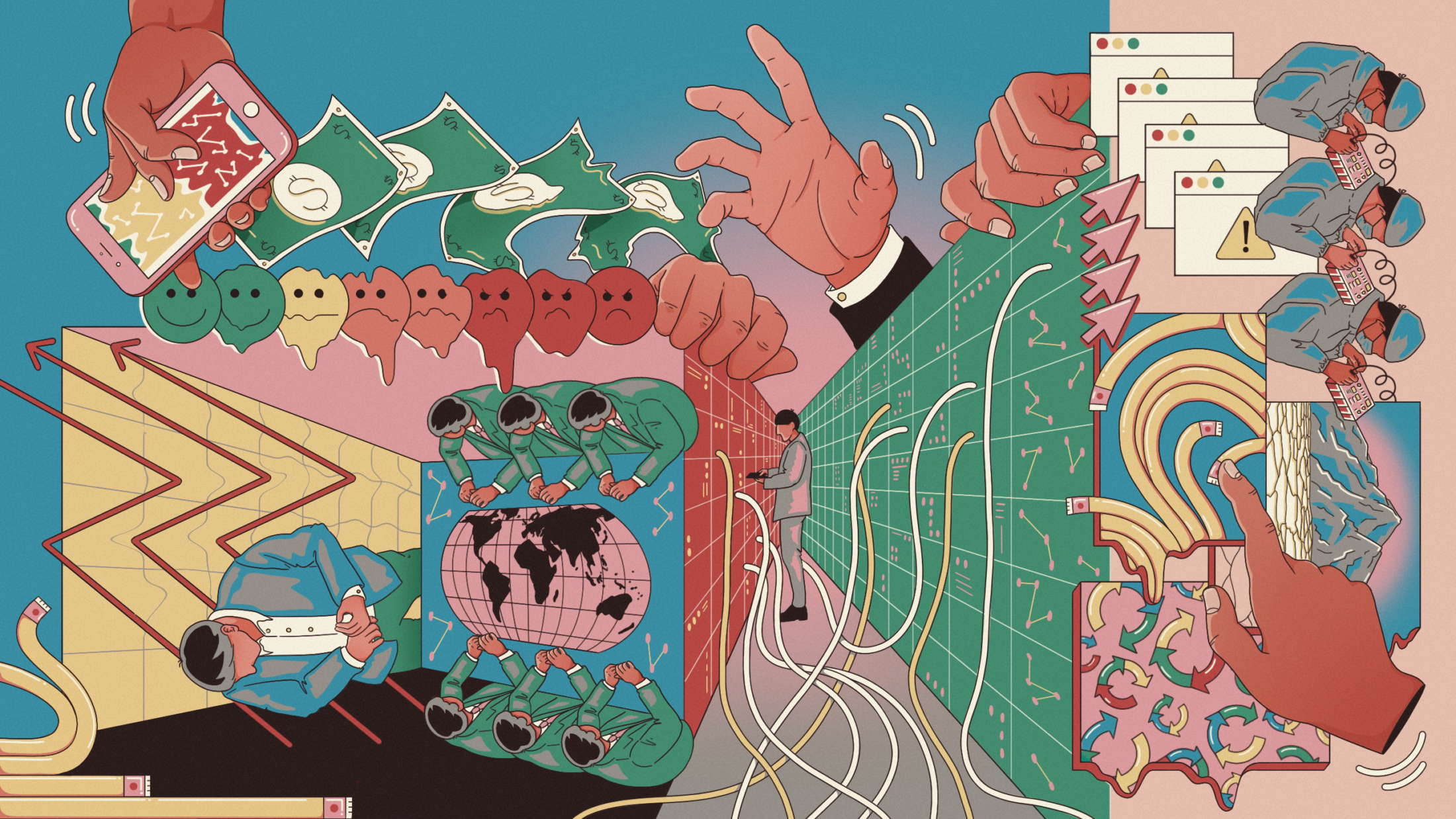

DSA Day and platform risks

Got Complaints? Want Data? Digital Service Coordinators will have your back – or will they?

The Digital Services Act (DSA) is the EU’s new regulation against risks from online platforms and search engines. It has been in effect since 2023, but 17 February 2024 marks “DSA Day,” on which many of the regulation’s most impactful provisions come into force.

The new provisions will (in theory) give EU citizens powers to strengthen EU citizens fundamental rights, researchers powers to access vital data, and every EU Member State its own national regulator to support this work.

However, the new provisions have to work in practice and on this note, it looks as though celebrations will be delayed for long after DSA Day.

Digital Services Coordinator: A new regulator for every EU Member State

One of the most important changes that 17 February brings is the creation of a Digital Services Coordinator (DSC) in every EU Member State. In some cases, these will be brand new bodies. In others, countries are giving new powers to existing entities, such as Germany which has designated the Federal Network Agency (Bundesnetzagentur, or BNetzA). The designation of DSCs unlocks a range of opportunities under the DSA.

For instance, users may have complaints about a platform unfairly taking down their content, restricting its visibility, or not responding appropriately after they requested moderation against harmful content. The DSA mandates that platforms provide effective complaint-handling systems, but users need other options should these systems be ineffective. To this end, DSCs will be able to make decisions on “out-of-court settlement bodies,” to whom users can go if they feel platforms have not handled their complaints appropriately. DSCs will also be able to designate “trusted flaggers,” whose content reports will be treated by platforms as trustworthy and therefore prioritized.

With the DSCs also comes an entirely new opportunity for data access and external scrutiny: data access for researchers, civil society, and journalists.

What we are doing now

“DSA Day” marks a point at which we should begin exercising new rights under the DSA. By doing so, we can push open questions and unresolved problems towards conclusions

At AlgorithmWatch, we will send a data access request to Microsoft via the German BNetzA to expand our research into Bing-generated election misinformation, ahead of the EU Parliament and next German regional elections in less than 4 months' time.

We also provide support for researchers and journalists to write and submit their own data access requests. If that could be you, please get in touch.

We have built a “systemic risk repository” where to register observed risk cases which may contravene the DSA, ranging from deep fakes in the Slovakian election to Amazon recommending books promoting Covid vaccine denialism. Contribute here: Online Systemic Risks under the DSA: Crowdsourced Evidence

And we share experiences of using new DSA provisions and relay these experiences to the EU Commission and DSCs to help efficient and effective rollout of full DSA provisions.

Data access requests

Recent years have seen a worrying shift in platforms towards closing off access to data. Meta was quietly deprecated Crowdtangle, the main tool used by researchers to monitor Facebook and Instagram. In 2023, after taking over Twitter (later renamed to X), Elon Musk replaced previously free data access with a $42,000 per month charge - a price that even Microsoft found too high. Lack of data access makes external research and understanding of these platforms extremely challenging.

Under the DSA, platforms must provide interfaces which give access to publicly accessible data. This includes, if technically possible, the access to real-time data to researchers who can ensure that this data is kept secure and used for public interest research. “Publicly accessible data” may sound as if it was available anyway. However, trying to find all the correct accounts to follow, and sift through all the data, is effectively impossible without adequate analytical tools. The new interfaces, which platforms have already begun implementing, could allow researchers to search for particular topics, rank content by engagement, or see which accounts are driving particular narratives. If they are properly implemented, these new online interfaces can be used to detect and combat information operations during elections.

From 17 February on, the DSCs are entitled to request specific data from platforms, in order to support monitoring and mitigating “systemic risks.” Moreover, researchers can also access such data via sending a request through a DSC. This data can include internal content and metrics that would previously have been visible only to platforms.

There are limitations to this new power. DSCs must approve (“vet”) applications and researchers to ensure that their research is appropriate – in particular, that the data is necessary to address a question related to systemic risks as defined by the DSA. Platforms can also challenge data access requests on grounds that they do not have the data or that there could be issues with security or trade secrets, leading to negotiations over alternative options with DSCs.

Sounds good - what are the issues?

Any regulation needs implementing and can expect initial teething problems. But in this case, there may be very little real change any time soon. The full implementation of the DSA face severe practical issues.

Many of the most important provisions of the DSA still require clarity. What, for instance, have researchers to do to ensure that their data access requests will be approved by DSCs? Also, many DSCs build up their capabilities too slowly and will simply not be ready for their task by 17 February. This applies to the German Bundesnetzagentur but also to the Irish agency despite it being at the forefront of requesting data from some of the largest platforms.

But time is of the essence here. Right now, we are facing ongoing Russian aggression against the West, particularly manifested against Ukraine but also in information operations against European politics and civic discourse. The conflict in Gaza has also spilled over into online spaces, with dangers of hate speech, disinformation, and unwarranted censorship. And 2024 sees a series of extremely important elections - including the EU Parliament elections in June - colliding with risks arising from generative AI. In such a context, it is deeply concerning that the timeline for a really effective DSA remains so uncertain.

Read more on our policy & advocacy work on the Digital Services Act.